The boom in shale gas resource acquisitions and development in North America over the past three years has brought a formerly niche play into the spotlight. Once primarily the province of under-capitalized independent producers who refined horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology to tap into the once-marginal tight gas reservoirs in Appalachia, the Central U.S. and Western Canada, the massive reserve has now sparked attention from the major industry players. ExxonMobil, through its acquisition of XTO Energy in 2010, other supermajors, and a host of gas-short Asian players have since taken positions in the U.S. and Canadian shale gas play, with total capital commitments exceeding $100 billion.

The boom in shale gas resource acquisitions and development in North America over the past three years has brought a formerly niche play into the spotlight. Once primarily the province of under-capitalized independent producers who refined horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology to tap into the once-marginal tight gas reservoirs in Appalachia, the Central U.S. and Western Canada, the massive reserve has now sparked attention from the major industry players. ExxonMobil, through its acquisition of XTO Energy in 2010, other supermajors, and a host of gas-short Asian players have since taken positions in the U.S. and Canadian shale gas play, with total capital commitments exceeding $100 billion.

Some of the best success stories today are of companies that are aggressively pursuing ownable ways to grow their businesses in markets characterized by intense competition, if not spirited rivalries. For example:

While the long term strategic merits of this massive inflow of capital remain unclear, the short-term effects have been profound. The focus of North American natural gas production has shifted to developing shale gas resources at a frenetic pace, with U.S. shale gas output growing from 1.5 TCF in 2007 to 7.8 TCF in 2011, inflicting massive change on the landscape of the North American gas industry.

And this is only the beginning. The U.S. Energy Department (DOE) forecasts shale gas production alone will grow to nearly 13 TCF by 2025, becoming 45% of total U.S. supply, with tight sands adding another 23%. From a global market perspective, U.S. net gas imports peaked at 3.6 TCF in 2007 and have declined steadily, to 1.5 TCF in 2012. However, the DOE projects that the United States will become a net exporter of natural gas by 2020, directly as a result of shale gas commercialization.

Further evidence of the boom is apparent in natural gas transportation infrastructure. In the early 2000s, some 50 LNG import terminal projects were on the drawing board in the United States, though only eight were built. Today, 13 LNG terminals are operating in North America, and as the focus turns to exporting, several import facilities are adding liquefaction capacity to reverse their originally-intended use.

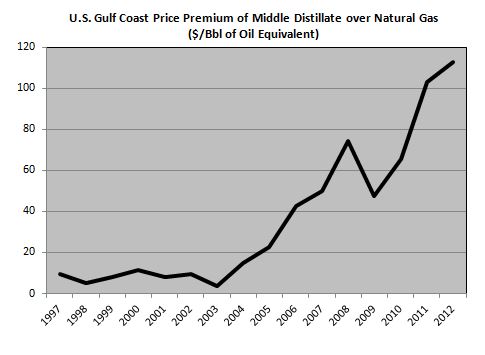

This fundamental shift in continental gas dynamics has also been manifested in pricing, with historically high differentials now existing between oil products and natural gas.

Figure 1: The price premium of middle distillate over natural gas has increased sharply since mid-2009.

Given the large volume of potential gas supply that has been shut-in or undeveloped in North America due to weakness in pricing, the high spread between oil and gas prices is expected to become the industry norm until longer-term, demand-side response can bring some equilibrium to the market. In addition to possible LNG exports, other market-side actions that may bring about balance include:

- Replacement and displacement of coal-fired simple-cycle power plants by combined-cycle gas units

- Reactivation and refurbishment of gas-based ammonia and methanol plants

- Proposals for new North American gas-to-liquids (GTL) plants

GTL plants, which require a large and sustainable premium between oil and gas prices, are perhaps the most salient indicator of the changing North American gas paradigm. To date, these plants have been located exclusively where gas resources are large and low-cost (Qatar and Malaysia), or where reliance on domestic resources was paramount (South Africa and New Zealand) to ensure security of supply. But today, two GTL proposals are on the drawing board in North America, both lead by Sasol, a leading player in GTL technology. While the principal objective of GTL technology is the production of essentially sulfur-free petroleum fuels, such as middle distillates and naphtha, an intermediate product of the Fischer-Tropsch condensation process is long-chain paraffinic waxes, which may be hydrocracked to produce ultra-high viscosity index (UHVI) lubricant base stocks in the Group III+ category. These UHVI base stocks are becoming much more in demand as the passenger car motor oil (PCMO) market around the world moves toward premium lubricants.

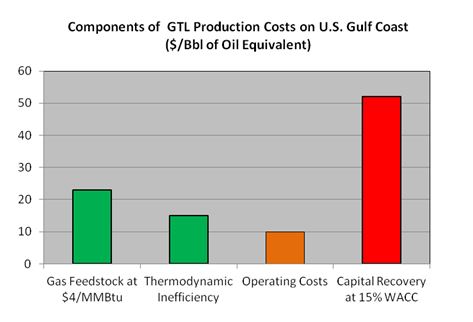

The capital-intensity of GTL projects has fluctuated wildly, from around $25-30,000 per daily barrel in 2000 to more than $100,000 (the reported final cost of Shell’s Pearl project in Qatar) as capacity pressures on the global engineering/procurement/construction (EPC) industry became severe in the mid-2000s.

This massive cost escalation had a salient impact on the GTL industry and was one of the factors that led to the cancellation of ExxonMobil’s proposed Palm project in Qatar, the cost of which tripled in only a few years. Facing a similar surge in cost, Shell reports the final bill on its Pearl plant in Qatar also more than tripled from an estimated $5 billion in 2003 to a final cost upon start-up in 2011 of $18-19 billion. Sasol’s recently-announced GTL project on the Louisiana Gulf Coast is expected to outpace both Qatar plants, costing $115,000-130,000 per daily barrel.

At current Henry Hub gas prices of around $4/MMBtu, Sasol’s plant would require sustainable oil-to-gas premiums of $70-85/Bbl over the cost of feedstock to support that investment. While current oil-to-gas premiums support that required differential, committing in excess of $10 billion to projects with input-to-output price differentials that are subject to high commodity basis risk certainly requires deep pockets, patience, and exceptional risk management skills.

Figure 2: With gas feedstock comprising nearly one-fourth of GTL production costs,

Sasol’s plant requires sustainable oil-to-gas premiums in excess of $70/Bbl over the cost of feedstock.

However, a secondary consideration of GTL plant design lies in the potential to channel some portion of paraffinic wax produced from Fischer-Tropsch (F-T) condensation toward the production of very high quality (Group III) lubricant base stocks. Driven by technical requirements for higher quality automotive lubricants, among other factors, Group III base stock demand is expected to grow at about 12% CAGR over the next 10 years, making the cost-benefit of adding Group III production advantageous.

While fuel and base stock production in GTL plants requires the hydrocracking of intermediate waxy streams under different operating modes, it’s not exceptionally expensive to add base stocks capacity to fuels-oriented GTL plants. Though conventional Group II base stock plants that use hydrocracking and catalytic dewaxing can, in theory, produce Group III stocks, this requires high-severity operation of the hydrocracker to increase viscosity index, resulting in significant loss in base oil yield. Therefore, most recent Group III production has been based on fuel hydrocracker bottoms (hydrowax).

On the other hand, because GTL-derived base stocks technology takes advantage of the fact that a majority of the F T condensation liquids are typically of a waxy nature, the production of GTL-derived base stocks is decided by the operational strategy instead of the additional process complexity. In other words, fuel-to-base stock pricing differentials and market conditions drive the wax conversion mode.

As a result, the incremental cost of adding the necessary wax isomerization unit at the back end of the GTL fuels mega plant is relatively insignificant. Sasol’s 96,000 BD GTL project at Lake Charles, LA, has an expected price tag of $11-14 billion; adding a complete 16,000 BD Class III+ base stocks production unit at an additional cost of $350-400 million (including off sites) increases total capex by only 3%, but provides operational flexibility to arbitrage base stock-to-distillate spreads in the market.

If GTL becomes embedded in the mainstream refined products supply as a function of sustained high oil/natural gas price differentials and a learning curve reduction in new facility capital-intensity, GTL plants will begin to put pressure on conventional refinery margins, increasing the economic incentive for channeling more waxy streams to value-added base stock manufacturing. This enhanced production of UHVI base stock streams will incentivize lubricant blenders to accelerate substitution of these materials into advanced PCMO formulations, which will precipitate the shutdown of old, small Group I solvent plants in Europe and North America, as well as higher cost Group II plants. Group I demand is already expected to drop by 20% to 30% over the next few years, and a supply push from GTL-based UHVI stocks will accelerate that decline.

Will UHVI gas-based lubricants ever completely displace conventional oil-derived blending stocks? Very unlikely, in Kline’s view, since GTL base stocks are primarily focused on high-performance automotive applications (GTL base stocks are not designed to compete in industrial and related heavy-duty applications). Moreover, the embedded capacity in existing and planned oil-based Group II and III capacity will be difficult to displace until and unless oil-to-gas price premiums continue to grow and are sustained at those levels. Nevertheless, GTL-derived base stocks should play an increasingly important role in the premium end of the market.

Given the huge cost of GTL plants, supply of GTL-derived base stocks will be confined to a very limited “club” (whose only member today is Shell). Sasol will join that club, along with potentially other large, well-capitalized major energy providers.

Where does that leave independents that don’t have the resources to play in GTL? The growth in GTL base stocks supply will ensure that this product will emerge from the shadows of an internally-captive supply within Shell’s system to one with a rapidly-growing merchant market where it will compete directly with conventional oil-based Group II and Group III base stocks. Key players who may take advantage of this source of new supply are large lubricant marketers who are not significantly backward-integrated into base stock supply, such as BP/Castrol, Fuchs, and Ashland/Valvoline, as well as large NOCs who wish to lead advanced lubricant formulations in their home markets, but do not wish to assume the costs and risks associated with GTL investments.